Green Packaging – How environmentally friendly are bioplastics?

The project Green Feedstocks for a Sustainable Chemistry (GreenFeed) is a collaboration between the DBFZ, the Wuppertal Institute, the Kassel Institute for Sustainability, and the KIT Institute of Technical Chemistry (ITC). The aim of the project was to identify pathways from today’s predominantly petrochemical-based plastics industry towards a circular and climate-neutral plastics industry in the chemical regions of Germany and Western Europe. To this end, various technical options were examined, including mechanical and chemical recycling, biopolymers, CO₂-based polymers, carbon capture and usage, as well as carbon capture and storage (CCU and CCS).

From here on, we focus exclusively on the production of biopolymers. Biopolymers can be produced from a range of raw materials, such as renewable resources, residual wood, or residual and waste materials. This means that polymers currently mostly made from fossil resources could potentially be partially replaced.

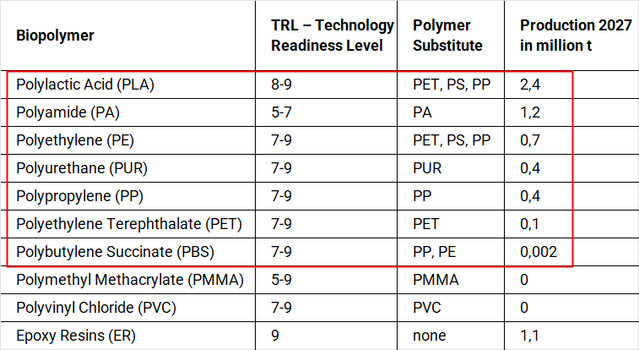

To assess both the environmental benefits and risks, life cycle assessments (LCAs) were carried out within the GreenFeed project for selected biopolymers. The selection of biopolymers was based on three criteria: technology readiness level (TRL; excluding those below TRL 5), the potential to replace petrochemically derived polymers for plastics production (excluding polymers with other application areas), and the expected global production capacity by 2027. From these production capacities, the following ranking emerged:

In addition, only biopolymers with a forecasted annual production of more than 1 kilotonne (kt) in 2027 were considered.

Assessment Methodology

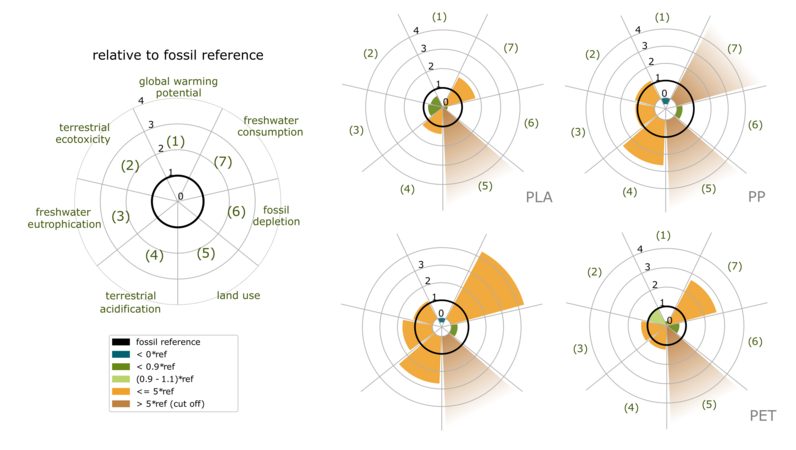

The environmental assessment was conducted following the life cycle assessment (LCA) method standardised in DIN standards 14040, 14044, and 16760. The impacts of the biopolymers were evaluated in terms of their global warming potential, land use, freshwater consumption, fossil resource use, eutrophication, acidification, and ecotoxicity.

Biogenic carbon dioxide was assessed according to ISO 14067, meaning it is assigned a greenhouse gas potential of –1 for 1 kg CO₂ removed from the atmosphere and +1 for 1 kg CO₂ released back into the atmosphere at the end of the life. The LCA was calculated for a cradle-to-gate system boundary, ending with the production of the biopolymer. The carbon dioxide bound within the material is accounted for as –1 kg CO₂ equivalent per kg CO₂. The functional unit applied is 1 kg of the biopolymer. The results for each biopolymer were then compared specifically with the corresponding fossil reference polymer it aims to replace.

The data used included mass and energy balances for polymer production, sourced from specialist literature, as well as emission data from the ecoinvent 3.10 database. Calculations were carried out using Umberto software (version 11.12.1).

Due to the very different application-specific uses of the biopolymers, direct comparisons are generally difficult. Therefore, only four biopolymers—PLA, HDPE, PP, and PET—commonly used in the food packaging industry, for example as bottle or cup materials, were considered here. Each was compared to its fossil-based reference polymer. These biopolymers are sugar-based, produced from various feedstocks (in this case: sugar beet, maize, and residual wood).

Findings from the Assessment

The LCA results showed that all biopolymers significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions compared to their fossil-based counterparts. The greatest reduction potential was found with bio-polypropylene, due to the lowest greenhouse gas emissions during processing and the highest CO₂ uptake and storage in the polymer. Here, a 179% reduction in greenhouse gases compared to fossil-based polypropylene could be achieved.

In addition to these significant reductions, all other biopolymers also show a reduced consumption of fossil resources compared to their fossil-based counterparts. In other environmental impact categories, the biopolymers perform differently depending on the feedstock used.

Overall, biopolymers that use sugar directly from sugar-containing biomass such as sugar beets are more advantageous in the impact categories investigated. The additional effort required to extract sugar from other types of biomass (e.g. starch- or lignocellulose-rich biomass) results in higher environmental impacts.

In a direct comparison of the four biopolymers, PLA performs best: besides significant savings in greenhouse gas emissions and fossil resource consumption, it also shows lower ecotoxicity than its fossil PET reference. For sugar beet-based PLA, the eutrophication potential is also lower than for PET (see figure). However, all the biopolymers examined still have potential for optimisation. Environmental impacts could be further reduced if renewable energy were used exclusively for power supply, heat and auxiliaries were recovered, and more environmentally friendly auxiliaries/chemicals were applied.

References

- Skoczinski et al. 2023: Pia Skoczinski, Michael Carus, Gillian Tweddle, Pauline Ruiz, Doris de Guzman, Jan Ravenstijn, Harald Käb, Nicolas Hark, Lara Dammer and Achim Raschka (2023) Bio-based Building Blocks and Polymers – Global Capacities, Production and Trends 2022-2027; https://doi.org/10.52548/CMZD8323

Further information about the Greenfeed project

Comments

No Comments

Write comment