Cracking the Code - The Multi-Layered Greenhouse Gas Balance of Hydrogen

Background

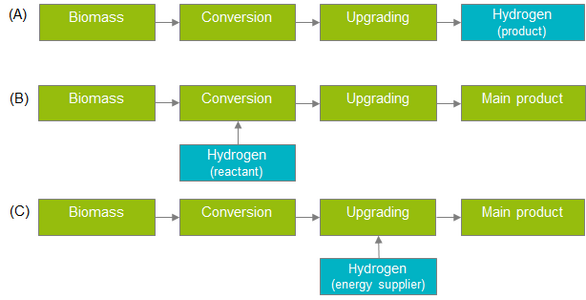

Hydrogen can play a key role as a product, an energy carrier, or a reactant in bio-based processes during the transition to more sustainable production systems (see Figure 1).

A crucial aspect of these processes is the greenhouse gas (GHG) balance, because hydrogen’s impact on the GHG balance of bio-based processes varies greatly depending on its source and method of production.

In addition to emissions from hydrogen production itself, emissions from transport and distribution (such as compression and losses through leakage) within the supply chain can also affect the overall GHG intensity — as can the climate impact of hydrogen as an indirect greenhouse gas.

The following section explains these three aspects in more detail.

GHG emissions from hydrogen production

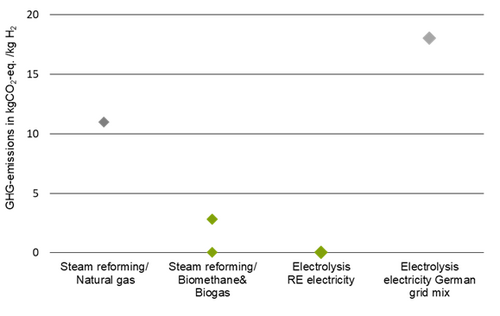

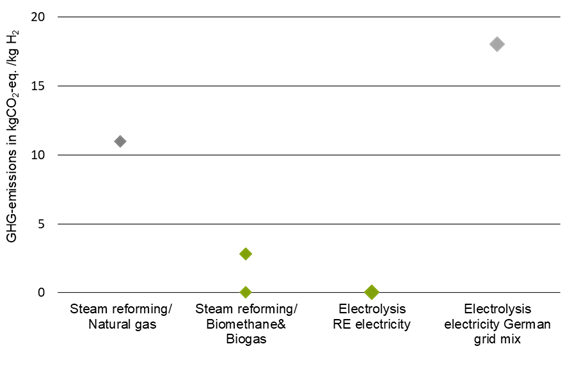

Hydrogen can be produced through different technologies and processes. As shown in Figure 2, this leads to a wide range of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions linked to its supply. The two most relevant current production methods — steam reforming and electrolysis — account for the majority of global hydrogen output (source: DBFZ Report 46). Steam reforming can use either fossil energy carriers such as coal and natural gas, or renewable sources like biogas and biomethane.

For electrolysis, GHG emissions mainly depend on the carbon footprint of the electricity used. Producing hydrogen with the German electricity mix would result in the highest emissions. In contrast, using electricity from renewable sources can bring emissions close to zero, provided that the infrastructure required to build the facilities is not included in the calculation.

GHG emissions from steam reforming of natural gas arise from multiple processes. First, burning fossil fuels to supply process heat releases CO₂. Second, in the reforming reaction itself, methane — the main component of natural gas — reacts with water to produce hydrogen and carbon dioxide. The CO₂ released here directly adds to the emissions tally. Additionally, emissions occur during the extraction, processing, and transport of natural gas.

Steam reforming of biogas for hydrogen production has similar emission sources, but with some important differences. It also produces hydrogen and CO₂ during reforming. However, the biogenic CO₂ released is not counted in the climate balance, since it is considered part of a natural cycle and does not permanently increase atmospheric CO₂ levels. On the other hand, emissions from producing the biogas itself still contribute to the overall GHG balance.

Example calculations for the process chains shown in Figure 1 can be found in the addendum to the methodological handbook “Substance-flow-oriented Accounting of Climate Gas Effects” [Oehmichen et al., under review].

Emissions from hydrogen transport/distribution → hydrogen losses

The following section on GHG emissions from hydrogen distribution within Germany is based on the special issue “Hydrogen Supply – Production and Logistics of Green Hydrogen.”

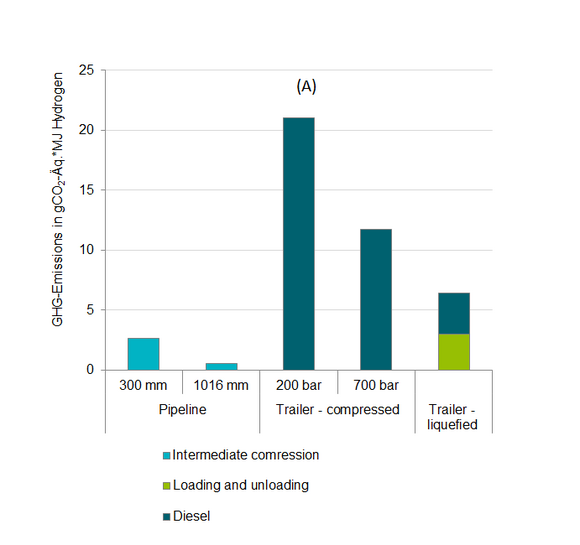

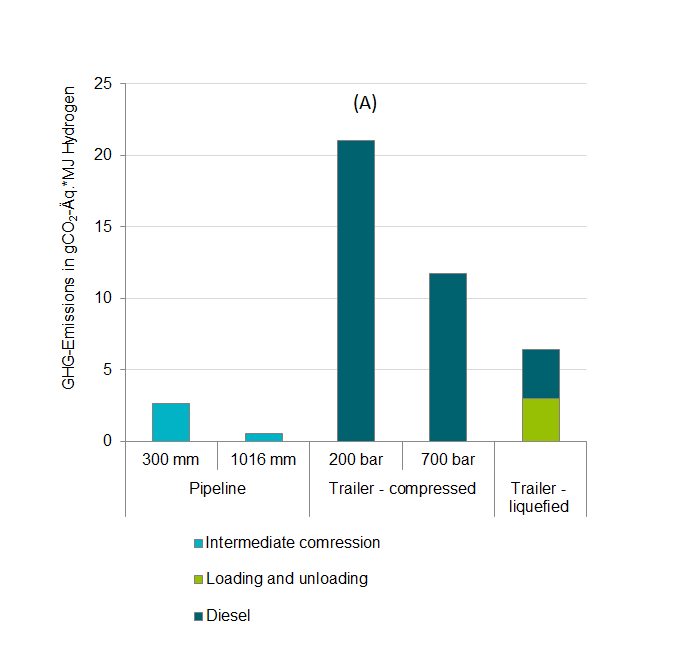

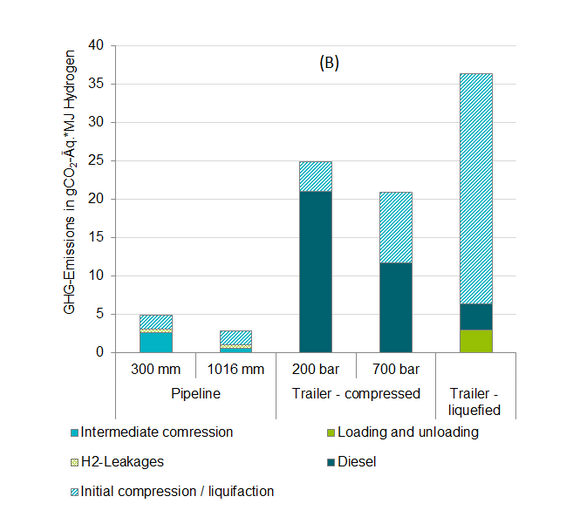

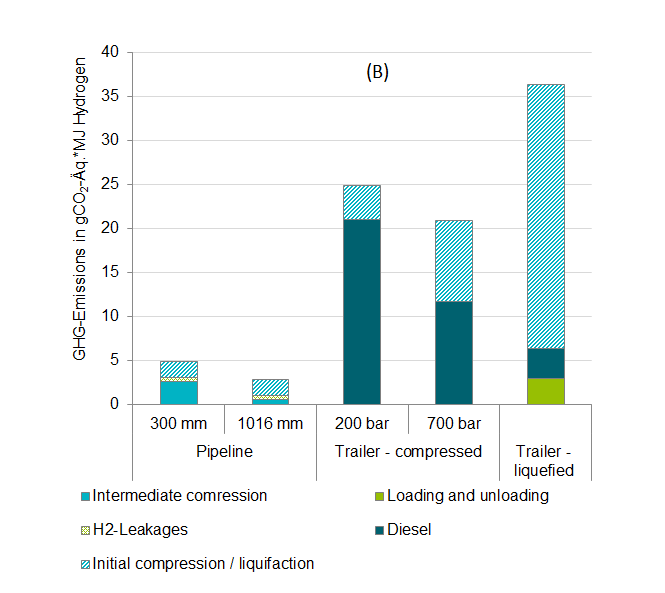

Hydrogen can be distributed either via pipelines or by trailer transport. In the latter case, it is transported in either compressed or liquefied form. For the GHG balance presented here, it is assumed that all logistical processes — such as intermediate compression and loading/unloading — use electricity from the German grid. The emissions from pipeline transport therefore depend heavily on the carbon intensity of the electricity used.

When comparing pipeline options, a pipeline with a diameter of 1016 mm has a significantly better emissions profile than one with a 300 mm diameter (Figure 10 (A)).

Overall, pipeline transport produces fewer emissions than transporting liquefied hydrogen by trailer, and far fewer than transporting compressed hydrogen by trailer. For the latter, high GHG emissions are mainly due to direct transport emissions from using fossil diesel. Figure 10 (B) illustrates the potential of using the German electricity mix for liquefaction and initial compression processes, which has a particularly strong effect on the emissions from distributing liquefied hydrogen by trailer.

Climate impact of hydrogen as an indirect greenhouse gas

The following section was compiled using information from the EPA as well as the publication by Sand et al. (2023).

Hydrogen is often described as a future-proof, climate-friendly energy option because it is not itself a greenhouse gas. However, this overlooks the fact that hydrogen can still have an indirect greenhouse effect. Hydrogen reacts with OH radicals, reducing their ability to break down greenhouse gases. As a result, the concentrations of methane, ozone, and water vapor in the atmosphere can increase (UBA, 2022).

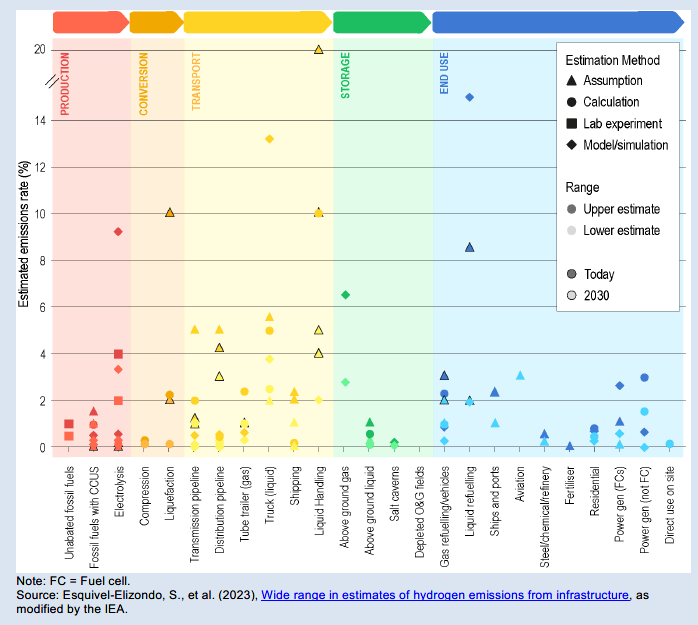

The release of hydrogen (e.g., through leaks during production, transport, and use) can therefore cause climate effects, even though hydrogen itself contains no carbon. Its climate impact strongly depends on where and how it is produced, transported, and used, as well as the exact emissions involved. For example, according to the IEA, 2024, transporting liquefied hydrogen by truck causes higher leakages—and thus higher emissions—than pipeline transport.

Hydrogen production via electrolysis causes no direct emissions, but depending on the electricity source, indirect emissions may still occur. Additionally, liquefaction and compression processes for transport can lead to energy losses of 45–70%, which in turn can increase the total greenhouse gas emissions of the final hydrogen product by a factor of 2 to 3.

There is no clear consensus on the exact greenhouse gas potential of hydrogen once it enters the atmosphere. This uncertainty arises because its climate impact is only indirect, caused by increased methane and ozone levels resulting from the reaction between H₂ and OH radicals. Over a 100-year time horizon, current studies estimate its global warming potential to be between 3 and 18.

References

- DBFZ Report 46: Dögnitz, Niels; Hauschild, Stephanie; Cyffka, Karl-Friedrich; Meisel, Kathleen; Dietrich, Sebastian; Müller-Langer, Franziska et al. (2022): Wasserstoff aus Biomasse. Kurzstudie im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft. Leipzig: DBFZ (DBFZ-Report, 46)

- Oehmichen, Katja; Majer, Stefan; Thrän, Daniela; Händler, Tina (2025): Wasserstoff in biobasierten Prozessketten - Beispiele zur Bilanzierung der THG-Emissionen im Förderprogramm: Addendum zum Methodenhandbuch "Stoffstromorientierte Bilanzierung der Klimagaseffekte": Begleitforschung Förderbereich "Energetische Biomassenutzung" (DBFZ) ¸ under review

- Dietrich, S.; Etzold, H.; Oehmichen, K.; Naumann, N. (2025). Wasserstoffbereitstellung | Erzeugung und Logistik von grünem Wasserstoff. Fokusheft im Projekt Pilot-SBG. Leipzig: DBFZ. 51 S. ISBN: 978-3-949807-34-3. DOI: 10.48480/aqdq-gr59.https://www.dbfz.de/projektseiten/pilot-sbg/publikationen/fokushefte

- UBA (2022): Ist Wasserstoff treibhausgasneutral? Stand des Wissens in Bezug auf diffuse Wasserstoffemissionen und ihre Treibhauswirkung; https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/479/dokumente/uba_ist_wasserstoff_treibhausgasneutral.pdf

- Sand, M., Skeie, R.B., Sandstad, M. et al. A multi-model assessment of the Global Warming Potential of hydrogen. Commun Earth Environ 4, 203 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-023-00857-8

- EPA https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/understanding-global-warming-potentials

- IEA (2024): Global hydrogen review 2024; https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2024

Further information on hydrogen involving DBFZ

Comments

No Comments

Write comment